List Comprehension

List comprehension (e.g. [expression for item in iterable if condition == True]) is faster than constructing a list with a loop. It can’t be used for all list constructions, such as where items depend on one another, but it should be used whenever possible.

Example Code

Rather than constructing a list with append() inside a loop

squares = []

for x in range(100):

squares.append(x**2)

Use a list comprehension

squares = [x**2 for x in range(100)]

Whilst being more concise and readable, it is also typically faster. The speed-up will depend on the length of the list, and complexity of it’s construction but is likely to be twice as fast.

List comprehension syntax can be nested to create two-dimensional lists, however using map() and zip() may create more readable code in these scenarios.

Example Benchmark

The below code provides a simple benchmark of creating a list of 100,000 consecutive integers using a three approaches.

from timeit import timeit

# Construct the list appending each item individually

def list_append():

li = []

for i in range(100000):

li.append(i)

# Construct the list by preallocating it, before setting each item to the correct value

def list_preallocate():

li = [0]*100000

for i in range(100000):

li[i] = i

# Construct the list using list comprehension

def list_comprehension():

li = [i for i in range(100000)]

repeats = 1000

print(f"Append: {timeit(list_append, number=repeats):.2f}ms")

print(f"Preallocate: {timeit(list_preallocate, number=repeats):.2f}ms")

print(f"Comprehension: {timeit(list_comprehension, number=repeats):.2f}ms")

In testing this produced the following results

list_append: 3.50ms

list_preallocate: 2.48ms

list_comprehension: 1.69ms

Using list comprehension was over 2x faster than using a loop and append().

The Technical Detail

List comprehension is likely faster than using loops and append, because the syntax is more constrained allowing greater optimisation within the Python back-end.

How Lists Are Implemented

Lists are implemented as a form of dynamic array found within many programming languages by different names (C++: std::vector, Java: ArrayList, R: vector, Julia: Vector).

They allow direct and sequential element access, with the convenience to append items.

This is achieved by internally storing items in a static array. This array however can be longer than the list, so the current length of the list is stored alongside the array. When an item is appended, the list checks whether it has enough spare space to add the item to the end. If it doesn’t, it will re-allocate a larger array, copy across the elements, and deallocate the old array. The item to be appended is then copied to the end and the counter which tracks the list’s length is incremented.

The amount the internal array grows by is dependent on the particular list implementation’s growth factor. CPython for example uses newsize + (newsize >> 3) + 6, which works out to an over allocation of roughly ~12.5%.

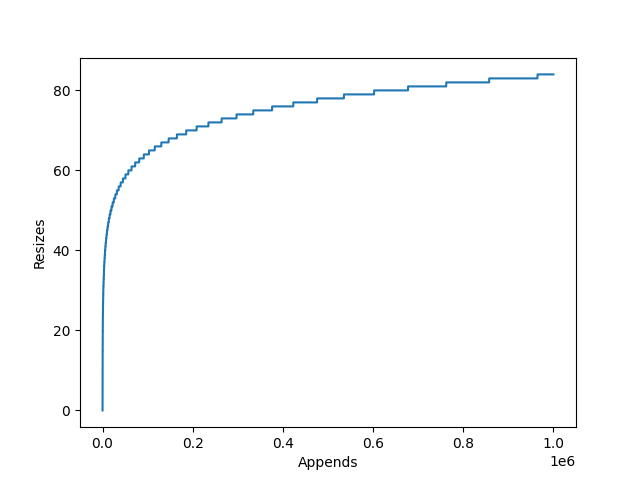

The relationship between the number of appends to an empty list, and the number of internal resizes in CPython.

This has two implications:

- If you are creating large static lists, they will use upto 12.5% excess memory.

- If you are growing a list with

append(), there will be large amounts of redundant allocations and copies as the list grows.

Both of which will result in slower code.